The role of

water composition on whisky flavours

Introduction:

A couple of years ago, I wrote a report on the influence of peat composition on the flavours of single malts (see Peat_smoke_whisky.html). Recently, I discovered a thesis published in 2008 by Craig A. Wilson on “The Role of Water Composition on Malt Spirit Quality” done at the International Centre for Brewing and Distilling, Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh Scotland. Any quote or illustrations used in this article are extracted from C.A. Wilson thesis.

The purpose of this article is to extract key facts from his work, to look at his results and conclusions critically using whenever possible a layman language.

Objective

of the thesis:

Water is one of the base ingredients of whisky production (together with yeast, barley and eventually peat) and used in large quantities (estimated to 30-40 million cubic meters per year in Scotland for process and cooling). Limited scientific data are available on the effects of water on the final products. Several companies are using the quality of their water to explain the excellence of their products, without scientific evidences. How important is the impact of the water on the distilled spirit?

CA Wilsons aims were to evaluate differences in the organic (e.g., vegetal extracts such a peat elements present in the process water) and inorganic (e.g., salts such as sodium, calcium or sulphate) composition of water used in the making of malt whisky at the distilleries of Teaninich, Clynelish, Glen Ord, Linkwood, Glenlossie, Talisker, Caol Ila, Bowmore, Lagavulin and Glenkinchie, from a chemical and physical point of view, as well as from a sensory perspective.

The choice of the distilleries is relevant, since it covers the different geological regions of Scotland as well as different types of water sources (e.g., from a loch or burn, hard or soft).

Part

1: Analysis of process water

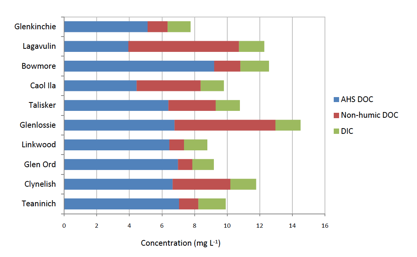

The humic composition indicated differences consistent with the location of the distillation. The composition of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and inorganic carbons (DIC) varied between the distilleries (see Figure below), with surface water showing the highest levels. However, no clear relationships between water sources and proportion of organic compounds could be made.

He summarizes his results as follows “In conclusion, marked differences existed between distillery process waters on the basis of organic content, chiefly determined by geographical location, type of water source and surrounding vegetation. Ionic content of process waters also varied according to location, in addition to underlying geology, although variation was limited in comparison with waters used by the brewing industry. However, chemical characterisation of process water gives little information in isolation.”

Part

2: Analysis of New Make Spirits Produced Using Industrial Process Waters

CA Wilson concluded in Part 1 that differences in water composition (from a salt and organic point of view) were different between the different distilleries. But does these differences results in different flavour profile (sensorial experience)?

In order to answer these questions, he set up a laboratory scale whisky making process.

Briefly, he produced a mash made from Optic barley and fermented the resulting wort with Quest M type yeast for 60 hours and distilled the spirit twice using a glassware distillation apparatus containing copper wire (“sacrificial copper”) to mimic the industrial process. For consistency, the spirit cut was based on volume and not on strength, as done in the distilleries.

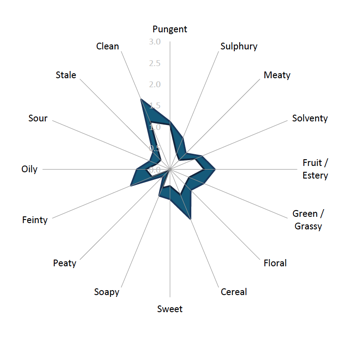

The sensory evaluation of spirits made from the different waters indicated statistically significant differences for the following attributes (flavours): sulphury, meaty, green/grassy, cereal, sweet, feinty and clean (see Figure below with the range of values). These attributes are the ones defined by the flavour whisky wheel and were assessed by a trained panel of 21 assessors.

No significant correlations could be made between ionic content (e.g. hard vs soft water) and sensory character.

He concluded that “Differences in sensory character were found to relate to the geographical source of the process water, with Speyside and Island waters producing heavier spirits, whereas Islay, Highland and to a lesser degree, Lowland waters produced lighter, sweeter spirits. A potential inverse proportionality between process water humic substance content and spirit ‘heaviness’ was proposed, although the site with the highest overall organic carbon levels in process water was shown to produce a ‘heavy’ spirit character and that (…) the peaty attribute scored low in all samples, proving peaty character is not sourced from water, but exclusively from the burning of peat during malt kilning.”

Part

3: Production of New-make Spirit Using Artificially Spiked Waters

In this part 3, the author wanted to

evaluate the effects of different ionic and organic species in isolation, since

those different species “may affect spirit flavour either through

direct flavour impacts or by affecting the mashing and fermentation processes

and the subsequent distillation”.

Inorganic

species:

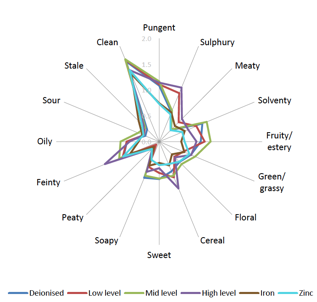

Using spiked

waters (i.e., water with added chemical ions), with different levels of

inorganic species “significant variances

were observed for cereal, feinty, meaty, oily and

sulphury attributes” as illustrated in the figure below:

CA Wilson

explanation is the following one: “this

being in part as a consequence of carrying out spirit cuts on the basis of

volume and differences in levels of copper contact in the lyne

arm”.

In terms of

mashing, fermentation and alcohol yield, no significant differences were

observed under the experimental conditions. By looking at the

concentration-time curve profiles of evaluated chemicals, at least for some of

them (e.g., butanedione), the values look very

different at 24h vs 48 or 60 h.

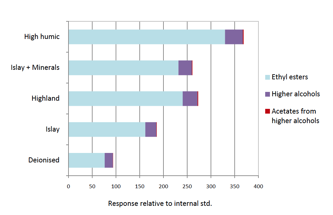

Organic species:

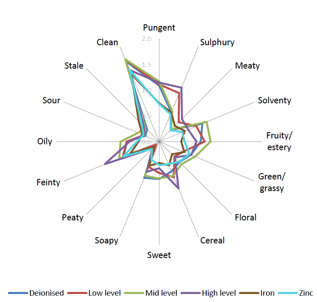

As for inorganic

species, water was spiked with different amounts of humic

substances extracted from the peat. Samples representative of Highlands, Islay

and artificially high humic levels were prepared and

new make spirit produced. The sensory analysis showed significant differences for

cereal, clean, meaty, stale and sweet attributes. The difference between the

samples is graphically presented below in the spider graph and the

concentrations in bar chart.

CA Wilson

conclusions for the organic species are the following ones:

“Overall, the sensory profile of spirits made from

peated waters differed in character from those made from deionised water, with

some variation present between samples varying in levels of peatiness in water

and composition of peat-derived compounds. Spirits made from waters containing

Highland peat showed a more complex character, whereas those made from waters

containing Islay peat scored lower for ‘heavy’ attributes, such as cereal and

meaty. (…) The role of inorganic ions in water was minimal at the

concentrations used in this study and that complexation

of ions was having a negligible effect on the fermentation process. (…) While

concentrations of syringyl-derived compounds in water

had shown some correlation with spirit character when using industrial process

waters to produce spirit, this was not replicated when using artificially-spiked

waters. Moreover, no significant correlation was found between levels of other humic substance classes and sensory character. “

The last statement

is rather surprising or even contradictory, since he mentioned that water has a

minimal but significant sensory effects when doing lab scale distillation but

he concludes later that with the exception of syringly-derived

compounds, organic compounds showed no correlation with the sensory character.

My conclusion and discussion:

The objective is

this work is interesting, since the effect of water is often used by Press

Release (PR) agencies and publicity department to explain (at least partially)

the uniqueness of the single malts produced at a given distillery. However,

these statements are not based on scientific findings. Answering the effect of

water on spirit is not an easy task and the approach from CA Wilson is scientifically

sound. It had however several limitations:

-

First

from a technical (physical-chemical) point of view, since no methods are

available to quantify simultaneously the different compounds (organic and

inorganic) present in the water and some compromise had to be made (e.g.,

temperature of pyrolysis). Therefore, several compounds might not have been

detected but could play a relevant role at the sensorial level.

-

Secondly, distillation was carried on in

a glassware distillation apparatus with sacrificial copper (somewhat like in a

Coffey Still) instead of a small copper post still and thus might result to

differences compared to copper pot stills.

-

Thirdly

in the impossibility to cut the spirit based on alcohol strength as in

industrial processes, in order to make his comparison. While sensory effects

were made on spike water, I wished he pushed his experimentations further in

order to establish some dose-response effects, e.g., by testing much higher

concentrations of organic matter until clearer effects are observed.

-

In

addition, sensory evaluation was tested with a 60 h

fermentation. Some distilleries are

fermenting the wort for 48 and others for about 70 h. Based on the different

concentration-time curves, other sensory effects might have seen at other

fermentation time, especially for shorter fermentations.

-

Finally,

a discussion on limitations (limits of quantification) of the analytical

methods used and in comparison with sensory thresholds would have been

appreciated.

By conducting

first a chemical analysis and then testing spike waters, this allowed the

author to confirm the results from the statistical comparisons. Extensive use

of the statistical approach PCA (Principal Components Analysis) was made, but

some discussions on its limitations given the complexity and systems used would

have been appreciated.

The take home message from this work is:

-

The

taste of peat comes exclusively from the kilning and not from the water

-

The

organic composition of water affects the following sensory attributes: cereal,

clean, meaty, stale and sweet.

-

Inorganic

composition has no sensory effect on the spirit under the tested conditions.

-

This

work was based on water made on representative Scotch single malt distilleries

but does not extrapolate to effects of water AFTER the distillation process

(e.g., during the reduction or whisky tasting).

Remark: These

conclusions are made in the context of the whisky production. At the level of

brewing, differences were notes, but with limited impact on whisky, since

distillation take place in the whisky production.

Slainte

Text: Dr P. Brossard, 27 July 2014.